An Overview Of Guinea Pig Biology and Breeding

Species and genetic characteristics:

'Guinea pig' often refers to the domestic guinea pig Cavia porcellus. There are 5 other kinds of guinea pigs, all wild species that live in South America: Cavia aperea, Cavia fulgida, Cavia intermedia, Cavia magna, and Cavia tschudii.

Cavia porcellus was created through domestication over several thousand years in pre-Colombian South America, reportedly in the Central Andes. It was raised primarily for meat production. The first archaeological evidence of human use of guinea pigs dates to about 8,000 BC (10,000 years ago), and the domestication began at least 5,000 years ago.

Guinea pigs and most (possibly all) of the Caviidae family are unique among rodents in that dietary vitamin C is obligatory. Like humans, they can't synthesize vitamin C due to a mutated gene for L-gulonolactone oxidase.

In the years before mitochondrial genetic analysis was possible, it was thought that Cavia aperea was the genetic parent species to C. porcellus. Its full species name during that time was Cavia aperea f. porcellus. A 2004 genetic analysis showed that C. aperea was actually one step removed from a genetic group that contains both C. porcellus and C. tschudii. The analysis suggests that there may have been a wild progenitor guinea pig species from which both C. porcellus and C. tschudii are descended.

Figure 3 from Spotorno AE, Valladares JP, Marin JC, Zeballos H. (2004) Molecular diversity among domestic guinea-pigs (Cavia porcellus)

and their close phylogenetic relationship with the Andean wild species Cavia tschudii

References to "guinea pigs" below all refer to C. porcellus.

Female guinea pigs are called "sows", and males are called "boars". There are different kinds of guinea pigs, such as laboratory-specific strains with specific genetic characteristics, pet types with varying coat types and colors, and meat production types.

Laboratory strain guinea pig boars are described as being between 900g - 1000g in weight on average, with sows between 700g - 900g. Outcrossed pet-bred individuals in my experience can be larger than this, such as 1.5 kg in males and over 1 kg in females. The largest types of guinea pigs, such as "Improved Cuy" or "Mejorado Cuy", were developed as meat-producing varieties and can be exceptionally large, as heavy as 3 kg (6.6 lbs).

In general, guinea pigs are not as genetically healthy as European livestock species. The primary cause of their genetic illness is the intense inbreeding that occurred during their domestication in pre-Colombian South America. Inbreeding of guinea pigs by modern-day breeders, when it occurs, can represent a further consolidation of genetic disease. A number of the diseases that guinea pigs are known for are what would be expected from genetic disease, such as their not-very-robust immune systems and the high rates of ovarian cysts in sows.

Opinion:

One way for a guinea pig breeder to combat the genetic disease inherent in this species is to prefer outcrossing and lean away from inbreeding.

In practice, I have seen certain of my guinea pigs with an inbred "show-breeding" background require as many as 4 generations of outcrossing to eliminate upper-respiratory-related immune system deficiencies (the sickness becoming evident at 3+ years of age). The decreased immune system health of my inbred show-types seemed clear as compared with my multi-generation outcrosses. The inbreds get sick easier and are harder to fix when they do.

Avoiding inbred breeding stock where possible is the sensible choice for a breeder who intends to breed pet guinea pigs as a business. Sickly breeding stock is not a business asset to anyone. Furthermore, breeding stock with a decreased tendency toward illness is the correct choice from a standpoint of animal welfare.

Notable: the original source of inbreeding-supporting philosophies espoused by some animal breeding associations appears to be the eugenics movements of the early 20th century.

Environment:

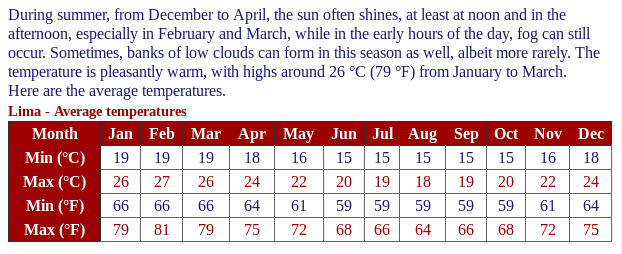

Temperature variation is not well-tolerated by guinea pigs. This corresponds with the narrow temperature range in their native habitat in South America. Table below is an example of one such area.

Example average temperatures. Source: climatestotravel.com, retrieved February 22, 2020.

There are almost no areas in the northern hemisphere where the climate supports maintaining guinea pigs outdoors on a continual basis with acceptable health and welfare results.

Guinea pigs are recommended to be housed in temperatures ranging from 64° to 79°F (18° to 26°C), with relative humidity between 30% and 70%. Air ventilation should allow for 10 to 15 fresh air changes per hour without causing drafts. The air changes must use fresh air, not recirculated, unless there is a filtration system in place to remove pathogens (such as a properly-managed hepa filter system). Same-day fluctuations in environmental conditions are to be minimized.

Extremes in temperature can kill guinea pigs. Excess heat can be detrimental to their health even for short periods of time, with temperatures above 75°F - 80°F potentially able to cause heat stress or stroke. Exposure of pregnant sows to temperatures of 80°F and above has been seen to cause birth defects in developing fetuses.

Social Groups

Guinea pigs' natural social groupings are properly described as harems comprised of one boar and a few sows (not "herd animals" as is sometimes reported in hobbyist literature).

Guinea pigs' natural social arrangement is boars and sows of varying ages co-habitating within indoor/outdoor/sheltered areas. Within these areas, multiple harems exist. Reportedly, boars need to be raised from birth within this kind of social arrangement in order to have behaviors that are compatible with it.

The relationships among the guinea pigs in this housing arrangement are more complex than simple harems would suggest. Changes in the alpha position in the male hierarchy can occur as the result of male-female associations, not just male-male competition.

It is more usual for pet breeders in the northern hemisphere to not use the above housing arrangement (multiple harems in one pen), instead maintaining harems separately and utilizing a single breeding boar.

Domestic guinea pigs' social associations and behaviors are different from those of wild species. Studies that examine the social behavior of wild guinea pigs are not great sources for understanding domestic guinea pig behavior.

Breeding and pregnancy

Use sows for breeding that have either previously delivered a litter, or are still young enough to be able to deliver their first litter before they reach 6 months of age. Sows that have not given birth while they are young frequently have their pelvic bones fuse together. The pelvis then stays closed at birthing time, making vaginal births impossible.

A sow's usable breeding life is something like 2 + years, or maybe 3 depending upon the individual sow and the breeding schedule she is on. Health issues can occur that necessitate earlier retirement, so not all sows are able to be used for the average duration.

Older sows (1.5 years +), assuming desirable mothering behavior, tend to be better mothers than younger sows. Older sows produce significantly more milk, which means the babies grow faster and larger litters are better-supported. On the other hand, young mothers that aren't making much milk sometimes create a situation where the breeder may choose to supplement the babies with an appropriate milk replacer to help maintain a good growth rate.

Sows with unusually small body size are not ideal for breeding. In my experience, they are more susceptible to nursing-induced hypocalcemia than regular or large-sized sows, and further, their smaller body size does not reliably translate into smaller fetus sizes. A small mother may end up carrying more proportional weight during her pregnancy than a larger-bodied one, making for more musculoskeletal and physiological stress and maybe increased potential for injuries.

From a pet breeding perspective, a boar's maximum breeding age can depend upon the breeders' needs and desires. A boar will generally be effective at covering a harem, including sows that may not be completely cooperative, until he's 3+ years old or something like that. An older boar who may not be vigorous enough to effectively pursue uncooperative sows (or is in danger of injuring himself doing so) may do fine when paired with a single sow with which he has a good relationship and is allowed to cover post-partum.

Non-pregnant guinea pig sows come into estrus about every 15 days.

Their pregnancies last a long time for a small animal -- on average between 64 - 66 days, or maybe you might see them go as far as 68 days. There are statistics quoting a range of 57 - 72 days for pregnancies but it's very uncommon to see the extreme high and low ends of that range. Litters born at the top and bottom of this time range are usually associated with problems.

Litters with more babies tend to be delivered earlier. Litters with fewer babies tend to be born later. Also, larger sows tend to deliver later than smaller sows, if you take into account how many babies they are carrying and relate it to the sow's size.

The longest normal pregnancy and delivery I ever saw was 70 days, the shortest was 63. The 70-day one was with a big 1.2 kg sow carrying a 3-baby litter.

At late pregnancy, sows can have huge abdomens because of all of the large babies inside. Due to carrying so much weight, they are prone to injuring their rear legs or hips if chased (this includes the sow running away from a human handler) or if harassed by other guinea pigs. In group housing, it's best to pay attention to the group's social interactions and be prepared to remove a pursued or harassed sow to an isolated birthing cage.

Late-pregnancy sows can die to fatal internal injuries if the sow is over-handled or held in the wrong positions. Handling during late pregnancy is to be minimized. If a late-pregnancy sow is being handled, it must be done carefully and correctly.

There is a catastrophic condition called pregnancy toxemia. The fetuses die quickly, plus you frequently lose the sow (in spite of rehabilitation efforts). |

Litters and Birthing

The average litter has 3 or 4 babies, but a

range of 2 through 5 is not uncommon. 6 or more is possible. Consistently super-sized litters of 6 or more may indicate a problem. In reproductively-normal sows, some of the fertilized fetuses disappear while they are still very small. I've read about some sows which have the apparent problem of this elimination not being very effective.

Litters sized 5 or more are generally undesirable from a breeding standpoint. Large litters are proportionally associated with an increase in stillbirths, result in smaller birth sizes in the babies, contribute to the likelihood of runts, and cause increased physiological stress on the sow during the pregnancy and while nursing.

Sows are susceptible to birthing difficulties (dystocia) due to the proportionally large size of their babies. Various kinds of malpresentation of fetuses inside the mother causes this as well.

The best situation for a sow having birthing difficulties is for the breeder to be in attendance and directly assist with the birthing process. In my experience, the breeder's correct and timely actions can usually save the situation. The sow not getting assistance with a difficult birth usually results in the death of the malpresenting or too-large baby (once it finally comes out) as well as deaths of some of the babies that are delivered after it, and can in some cases cause the death of the sow.

Babies and birthing aftermath

Newborn guinea pigs are very well-developed for newborn mammals. They are fully furred, with eyes open, and are able to see and hear. They are usually able to move around almost immediately, walk within a few hours, and run after a few more hours. The only guinea pig I have personally seen leap clear out of a cage was an unexpectedly-panicked 12 hour old baby. (Plop. It was stunned, but recovered quickly.)

Guinea pig sows usually expel placentas after all the births are complete, but sometimes placentas will come out in between babies, especially with larger litters. There is one placenta for each fetus if you don't take into account the possibility of identical twins sharing a placenta or strange, conjoined placentas. Usually, all of the placentas come out within a few hours, but I had one sow that held onto them for as long as 10 hours.

Sometimes, sows eat placentas. When they do this, they tend to eat them right after they pull them out. I have not seen them dig out and gobble down placentas that became buried in cage litter.

I'm not aware of a study where health outcomes were compared between sows that ate placentas and sows that did not. I wonder if this behavior exists because, during the evolution of wild guinea pigs, leaving placentas lying around would have attracted predators.

A breeder may not always be aware as to whether a sow has expelled all placentas. However, if a breeder is aware that a placenta has not been expelled after more than 12 hours has passed, that's the threshold where getting a veterinarian involved would be a good idea. A retained placenta will be visible to an experienced small-animal veterinarian on ultrasound. To my knowledge, retaining a placenta is likely to kill the sow (sooner or later), but I've never had this problem.

Feeding

In the northern hemisphere, guinea pig pellets that are formulated specifically for guinea pig breeding should be fed, in addition to feeding a meal of fresh vegetable and/or grass ("green feed") at least one time per day (two times per day on green feed is better).

The best guinea pig breeding pellets I am aware of are manufactured in 12+ kilogram bags for laboratories and other professional operations. They are around 23% protein. In contrast, guinea pig feed produced for retail sale (often in pretty bags) has been inferior as far as I've seen. A note: if the protein percent isn't listed on a package, it can be assumed to be 14%, which is inappropriate (in my opinion, 14% is not even optimal for a maintenance diet).

Especially for breeding animals, I can't recommend that anyone use retarded pellets, no matter how pretty the bag is or what they print on the bag to try to make a pet owner think that an otherwise low-grade 14%-protein pellet is actually amazing.

Hay must be available at all times, as well as water, which is to be provided in bottles with sipper tubes or an automatic watering system intended for use with guinea pigs.

For breeders in the northern hemisphere, all of the above food items should be considered necessities. It is not recommended to use pellets intended for other species such as rabbits -- guinea pigs have different nutritional requirements (such as a higher magnesium requirement, as just one, it's not only about vitamin C). Careless feeding not work well will this species. Guinea pigs are exotic domesticated rodents originally sourced from another region of the world, and its ancestral foods are not available in the northern hemisphere.

Other regions of the world, such as South America and Africa, can be different. Nutritious, safe, fresh-green feeds that meet guinea pig nutritional requirements, and are available year-round, may exist in those locales, and will be known to local breeders.

Tall fescue is a type of grass that is common in lawn mixes. Pregnant guinea pigs must not be fed tall fescue, or hay products that include tall fescue! In my experience, guinea pigs are susceptible to fescue toxicosis, and it's really bad when it happens. You could end up with horrible, premature, strange, shaking babies that aren't viable, and maybe the sow dies afterward, too. I saw this after I fed a sow overwinter using a hay product that was misrepresented to me as containing a small percentage of uninfected tall fescue. The generally large-bodied sow was healthy at the beginning of her pregnancy but she put on weight too slowly during the pregnancy, and then when the babies came, they were ridiculous as described above.

Definitely do not try to make guinea pigs subsist on grass in your yard all summer, as though they are sheep or something. Fescue toxicosis: avoid it like the plague.

Guinea pigs have no sense of the conservation of food and water. They are known for:

- pissing and pooping in food bowls, on top of the food

- scattering, trampling, and pissing on hay, rendering it

inedible

- spitting food particles into the sipper tubes of water

bottles

- trampling and scattering and pooping on green feed

- if they were given an open container of water such as a

bowl or dish, they would horribly foul it.

<< Back

Sources:

B.K. Kimura, M.J. LeFebvre, S.D. deFrance, H.I. Knodel, M.S. Turner, N.S. Fitzsimmons, S.M. Fitzpatrick, C.J. Mulligan. (2016). Origin of pre-Columbian guinea pigs from Caribbean archeological sites revealed through genetic analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 5 (2016) 442–452.

Yarto-Jaramillo, Enrique. (2015). Fowler's Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine. Volume 8, 2015, Pages 384-422

Rowe, D. L. and R. L. Honeycutt (2002). Phylogenetic relationships, ecological correlates, and molecular evolution within the Cavioidea (Mammalia, Rodentia). Molecular Biology and Evolution, 19:263-277.

Spotorno AE, Valladares JP, Marin JC, Zeballos H. (2004) Molecular diversity among domestic guinea-pigs (Cavia porcellus) and their close phylogenetic relationship with the Andean wild species Cavia tschudii. Revista Chilena De Historia Natural. 2004; 77.

Yamamoto, Dorothy (2015). "Section 4: On The Menu". Guinea Pig. London N1 7UX, UK: Reaktion Books.

Wing, E. S. (1977). Animal domestication in the Andes, in C. A. Reed (ed.) Origins of agriculture: 827-59. The Hague: Mouton Publishers.

Jacobs, William W. (1976). Male-female associations in the domestic guinea pig. Animal Learning & Behavior, 1976. Vol. 4 (lA). 77-83

Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press, Washington,1996.

Wagner, Joseph E.; Manning, Patrick J (1976). The Biology of the Guinea Pig. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-730050-4.

Lynn C. Anderson, Glen Otto, Kathleen R. Pritchett-Corning, Mark T. Whary (2016). Laboratory Animal Medicine, Third Edition.

Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-409527-4.

F A Fonteh, A T Niba, A C Kudi, J Tchoumboue and J Awah-Ndukum (2005). Influence of weaning age on the growth performance and survival of weaned guinea pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development 17(12).

First-hand information from the author's experience

Several discussions with one of the exotic animal specialists/researchers at the Helsinki University's veterinary hospital in Viikki